Time is running out for the Greek government, which needs to reach a deal on unpopular austerity measures if it is to secure a second EU/IMF bailout. German commentators argue the country has already suffered enough, saying what are needed now are measures to stimulate growth.

As the end game in Greece’s crunch bailout talks looms, frustrations are high on all sides. One deadline after another has passed as parties in the Greek coalition government have repeatedly postponed meetings.

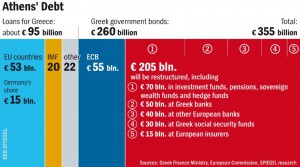

On Wednesday, leaders of the parties that make up Greece’s coalition government were finally studying a 50-page document laying out a draft deal on tough austerity measures, which had been drawn up by the so-called troika of the European Commission, European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund. Greek Prime Minister Lucas Papademos was due to meet leaders from the three parties in his coalition to discuss the deal later in the day.The government has to agree to the cutbacks if it wants to secure a €130 billion ($170 billion) bailout from the European Union and IMF, or it will be forced to default in March. The troika wants Athens to make new cuts in private-sector wages and pensions, lay off public-sector workers and cut health, pension and defense spending.

An agreement was originally supposed to have been reached on Sunday, but the talks between party leaders have been repeatedly delayed over the past three days. A meeting on Tuesday was postponed, supposedly because of missing paperwork. Once the coalition agrees on the deal in principle, it will be put to the Greek parliament. If reached, the deal is likely to prove unpopular with the Greek population, and some observers in Athens believe that the parties are deliberately stalling the talks to make it look as if they are driving a hard bargain with the troika.

‘We Can Handle an Exit of Greece’

German Chancellor Angela Merkel said Tuesday that it was possible an agreement would be reached by Thursday evening. She also spoke out, once again, against Greece’s leaving the euro zone. “I want Greece to keep the euro,” she said at an event in Berlin on Tuesday evening. “I will not participate in efforts to force Greece out of the euro zone.”

On the EU side, there is growing frustration with the delays in Athens. The lack of progress prompted European Commissioner Neelie Kroes to say that the euro zone could survive Greece’s departure. “When one member leaves, it doesn’t mean ‘man overboard,'” she told a Dutch newspaper in an interview published Tuesday. “They always said if a country is let go or asks to get out, then the whole edifice will collapse. But that’s simply not true.”

Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte also said that the euro zone could survive without Greece. “We can handle an exit of Greece,” he told a Dutch television station on Tuesday.

The mood in the Greek populace can be gauged by the fact that a German flag was burned in Athens during Tuesday’s general strike. There is resentment in Greece at the notion that the rest of the euro zone — particularly Germany — is imposing austerity measures on the country that are strangling its economy and hurting ordinary people. Unions called a general strike on Tuesday to protest the troika’s demands, and an estimated 20,000 people participated in demonstrations in Athens.

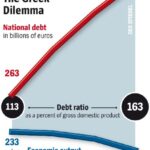

Meanwhile, talks between the Greek government and private-sector creditors over voluntary debt relief are also continuing. There, too, a deal seems elusive. The so-called haircut on Greek debt is another condition of the EU bailout. According to media reports, the current state of talks foresees a 70 percent haircut on Greek bonds held by private investors.

Time, in any case, is running out for Greece. EU officials said that the whole package must be agreed to with Athens and approved by the euro-zone member states, the ECB and the IMF before Feb. 15 in order to allow enough time for the debt swap. Greece needs to get the next tranche of bailout money by March 20, at the latest, if it is to meet its debt repayments and avoid default.

On Wednesday, most German commentators argue that Greece has already been squeezed dry. Now, they say, it is time to stimulate growth in the country.

The left-leaning Die Tageszeitung writes:

“In Germany, there is a widespread feeling that the Greeks must be to blame (for the fact that its situation isn’t improving). They are not economizing enough, are still earning too much and are simply not carrying out reforms, so the thinking goes. In Germany, resentment is rife, and there is a general suspicion that the Greeks simply can’t manage it.”

“But could the Germans? Would they survive a crisis like the one in Greece? … The Greeks are in their fourth year of a recession, and there’s no end in sight. Its economy will probably shrink by a total of 20 percent. If Germany was hit by a similar scenario, its economic output would fall by around €500 billion. This is simply unimaginable. Here, there is already a crisis if the federal government wants to cut €5 billion from its budget.”

“It is pointless to push the Greek economy over the edge through austerity. The victims are not only the Greeks, but also their foreign creditors, the other euro-zone members. Greece is going to cost money. Part of the emergency loans that the Europeans are giving the country will never be seen again. The only question is how high the losses will be. And even though it is counter-intuitive, the more generous the Europeans are now, the smaller the final write-downs are likely to be. They have to invest in growth in Greece.”

The center-left Süddeutsche Zeitung writes:

“Maybe if Greece collapses entirely, it will finally be able to find a common will to rebuild the country. There is certainly plenty that needs to be done. The public administration needs a complete overhaul, while the private sector needs more freedom to act. The cartels, which are partly responsible for the fact that many everyday goods are more expensive in Greece than in Germany, need to disappear. Athens will not succeed in doing all that by itself. Europe’s aid will remain desperately needed, otherwise a whole generation of Greeks could turn against the European project.”

“In the rich part of the EU, however, a sense of injustice has now set in. People are asking, for example, why Germany should support Greece yet again. If the Greeks had managed their economy better, goes the thinking, they would not be in such a deep mess now. This anger also has its justification, but it overlooks the fact that the monetary union did not create a union of equals. The Greek debt crisis was not caused just by exorbitant government spending, but also by a consumer shopping spree, which benefited German companies such as BMW and Bosch. Social justice requires that we also remember that fact.”

In a guest editorial for the business daily Handelsblatt, Jean Pisani-Ferry, director of the Brussels-based think tank Bruegel, writes:

“Europe is launching a new fiscal pact that will ensure countries adopt and implement strict budgetary rules. The assumption — especially in Germany — is that protecting countries from the pressure of the markets would hinder the necessary adjustments and reforms, and that only strong pressure will provide the necessary incentives to overcome internal political and social hurdles in order to reduce public spending and reform labor markets.”

“But this strategy is highly risky. It’s true that governments need incentives to act, but they also need to be able to show their citizens that reforms pay off. If, after a few months of fiscal adjustment and painful reforms, economic output is down, unemployment is higher and the outlook is grimmer than before, then governments could quickly lose public support. Then, the reforms could come to a halt, as we have seen in Greece.”

“We should beware of taking the wrong approach. It’s one thing to believe that governments only act under pressure and that societies only accept reforms if they see no alternative. But it is another to assume that progress can be made with reforms while the whole of southern Europe is struggling with a recession. Keeping southern Europe on a short leash is only a credible strategy if it is accompanied by a comprehensive and effective program to promote growth in the entire euro zone. … Weak growth in southern Europe could soon endanger the EU itself.”

The conservative Die Welt writes:

“It’s very obvious now that it’s already too late to save Greece through further bailout loans. In purely economic terms, the country should not have received any more loans for a long time already. They do nothing but simply postpone the inevitable bankruptcy. The Greek government has hardly complied with any of the requirements of the troika, and the pace of reform is far too slow.””But that is unlikely to stop politicians from transferring additional billions to Athens. It’s becoming increasingly clear what a bad position European leaders and finance ministers have maneuvered themselves into. If they pull the plug now, they will have to expect far greater write-offs than would have been the case just with private sector participation. German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble is hardly likely to risk that.”

“For today’s leaders, the simplest solution may be to kick the can down the road, making the problem increasingly large. For Europe, however, that is the wrong way. It would mean that tiny Greece would cause even greater damage to the continent.”